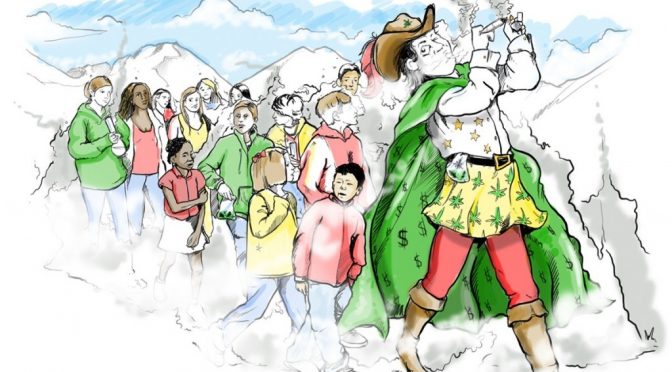

Smart Approaches to Marijuana (SAM) issued the following rebuttal to a paper by CPEAR, a group pushing nationwide legalization. The paper argues that youth marijuana usage does not go up after state legalization. We maintain that the fallout from high potency THC products on the teens’ use is the real issue. Several legalization states are now addressing the potency issues.

A new policy paper released on March 16, 2022 by the Coalition for Cannabis Policy, Education, and Regulation (CPEAR), funded by Molson Coors, Altria (Philip Morris), private cash and other companies is highly flawed and does not advance the discourse on the effect of state marijuana laws on youth marijuana use.

The alcohol and tobacco industry-backed industry group CPEAR is a regulatory-focused group that is partnered with and funded by industries that directly benefit from the legalization of marijuana. Some of their partner groups include: Altria, Molson Coors, and security, insurance, and convenience store associations.1 Their mission is to legalize marijuana nationally.

Summary

CPEAR’s assertion that marijuana legalization is not tied to increases in youth marijuana use is not supported by their evidence lumping all states together and looking at a national number—and several states have shown increases in youth use since legalization. CPEAR is a Big Tobacco-funded group whose mission is to commercialize marijuana and whose paying members will benefit from that policy change.

Background

On March 16, 2022, CPEAR released a paper alongside a forceful press release headline: “Cannabis Legalization Is Not Associated with Increases in Youth Use”.2 However, the content of the paper neither matches the definitiveness of the press release nor does it reflect the state of the science.

CPEAR’s discussion on the effect of state marijuana legalization on youth cannabis use is merely two sentences and makes just one reference––to national-level averages, which do not reveal any information about state-level changes.

CPEAR Policy Paper

The CPEAR Policy Paper asserts that, “…state legalization of cannabis has not, on average impacted the prevalence of cannabis use among adolescents”.2 However, the section’s sole citation is to national averages of 12 month prevalence of cannabis use for 8th, 10th, and 12th graders from 1975 to today.

It is true the national average of past year youth marijuana use has been relatively steady since the early 2000s. However, medical and recreational marijuana policies are set at the state level, and national averages––which group all states together––cannot indicate whether the states that legalized marijuana experienced an increase in youth marijuana use.

Assume, for argument, that recreational marijuana laws increase youth marijuana use. Youth marijuana use would then increase in states that legalized marijuana. However, if states that did not legalize marijuana experienced a secular decrease in youth marijuana use, the national average of youth marijuana could nevertheless decline over time. The evidence provided is a far cry from CPEAR’s claim that state marijuana legalization has not affected youth marijuana use.

The CPEAR paper then admits that, “a growing number of studies suggest that state legalized cannabis increases youth cannabis-related harms such as [cannabis use disorder], cannabis-related hospitalizations, and driving under the influence of cannabis”.2

This admission, however, is not mentioned in their press release.

The State of the Literature

While not all methodologically perfect, more rigorous academic studies at least compare youth marijuana use within legal marijuana (LM) before and after the policy is adopted and/or compare the trajectory of youth marijuana use in LM states to youth marijuana use in non-LM states. These studies have painted a much more nuanced picture of the relationship between state marijuana legalization and youth marijuana use. Importantly, as recreational marijuana legalization is a relatively new policy innovation (the first recreational marijuana dispensaries in the United States opened in 2014), virtually all studies to date have not had data to estimate precisely the effect of state marijuana legalization on youth marijuana use.

Washington, California, Alaska

Some recent studies nevertheless suggest that youth marijuana use may have increased in states that legalized recreational marijuana. For example, Cerdá et al. found that marijuana use increased 2.0% for 8th graders and 4.1% for 10th graders following Washington State’s recreational marijuana law (but no discernible change for Colorado).3 More recently, Paschall et al. found that California’s recreational marijuana law was associated with 18% and 23% increases in the likelihood of lifetime and past 30-day marijuana use among middle and high school students, respectively.4

Lee et al. found that, relative to Hawaii, the likelihood of high school lifetime and current marijuana use increased 29% and 34% after recreational marijuana was legalized in Alaska.5 Bailey and colleagues found nonmedical marijuana legalization among a large cohort of youth in Seattle, Washington, predicted a more than 6 times likelihood of self-reported past year marijuana and a more than 3 times likelihood for alcohol use among youth when controlling birth cohort, sex, race, and parent education, but was not significantly related to past-year cigarette use.6

Other studies admittedly have failed to find a significant relationship between state marijuana legalization and youth marijuana use. For example, a new study by Anderson et al. found no evidence of an association between recreational marijuana laws and youth marijuana use, though this study has received a good deal of methodological criticism.7 Midgette and Reuter used data from the Washington Healthy Youth Survey and found that after recreational legalization, marijuana use in Washington State followed a similar trajectory to states without recreational marijuana laws.8 This was not supported, by Bailey et al., who looked at Seattle only and found a sixfold likelihood increase in youth marijuana use post-legalization.

Conclusion

The literature on the effect of recreational marijuana laws on youth marijuana use is concerning—and at best mixed. It likely will not be resolved until longer-term, higher quality data is made available. Consequently, the debate on the effect of state marijuana legalization on youth marijuana use is far from resolved.

The limited evidence presented in the CPEAR paper does not meaningfully contribute to that discourse. On the other hand, as the CPEAR paper concedes, there is growing and substantial evidence that recreational marijuana laws are associated with increased marijuana-related harms among adolescents and young adults.9

The CPEAR press release headline––that recreational marijuana laws are not associated with youth marijuana use––should be ignored, and instead, policymakers and advocates should focus on the observed increase in marijuana-related harms among adolescents

More from SAM’s press release about the report.

References

1. CPEAR. Who We Are. Accessed March 17, 2022. https://www.cpear.org/who-we-are/

2. CPEAR. Cannabis Legalization Is Not Associated with Increases in Youth Use – Coalition for

Cannabis Policy, Education, and Regulation. Accessed March 17, 2022. https://web.archive. org/web/20220317164542/https://www.cpear.org/press-releases/2022/03/16/cpear releases-research-paper-on-cannabis-and-youth-use-prevention/

3. Cerdá M, Wall M, Feng T, et al. Association of State Recreational Marijuana Laws With Adolescent Marijuana Use. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(2):142-149. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.3624

4. Paschall MJ, García-Ramírez G, Grube JW. Recreational Marijuana Legalization and Use Among California Adolescents: Findings From a Statewide Survey. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2021;82(1):103-111. doi:10.15288/jsad.2021.82.103

5. Lee MH, Kim-Godwin YS, Hur H. Adolescents’ Marijuana Use Following Recreational Marijuana Legalization in Alaska and Hawaii. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2022 Jan;34(1):65-71. doi: 10.1177/10105395211044917. Epub 2021 Sep 11. PMID: 34514864.

6. Bailey JA, Epstein M, Roscoe JN, Oesterle S, Kosterman R, Hill KG. Marijuana Legalization and Youth Marijuana, Alcohol, and Cigarette Use and Norms. Am J Prev Med. 2020;59(3):309-316. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2020.04.008

7. Anderson DM, Rees DI, Sabia JJ, Safford S. Association of Marijuana Legalization With Marijuana Use Among US High School Students, 1993-2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(9):e2124638. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.24638

8. Midgette G, Reuter P. Has Cannabis Use Among Youth Increased After Changes in Its Legal Status? A Commentary on Use of Monitoring the Future for Analyses of Changes in State Cannabis Laws. Prev Sci. 2020;21(1):137-145. doi:10.1007/s11121-019-01068-4

9. Hosseini S, Oremus M. The Effect of Age of Initiation of Cannabis Use on Psychosis,

Depression, and Anxiety among Youth under 25 Years. Can J Psychiatry. 2019;64(5):304-312. doi:10.1177/0706743718809339