Read Part 1, Part 2, Part 3 and Part 4 of The Unraveling of Ryan. Permission is required to reproduce the story. Names are changed, but details are accurate.

As I was writing this story, Leah texted me from her husband’s bedside at Cedars-Sinai Hospital: “LA Times, front page article, ‘Cannabis Hedge Funds Rush to Join Green Rush.’” We both wanted to vomit. Our two sons are casualties of this “green rush” movement, a movement to profit from making today’s highly potent strains of marijuana — at the expense of our youth….and their families. We will never address America’s mental health crisis until we accept that marijuana is the trigger that starts too many young lives unraveling.

Leah’s husband, Lee, suffered a major medical crisis, as if losing their 20-year-old son 32 months ago to suicide wasn’t enough for the family. Ed and I met Lee and Leah in the grief series; the four of us share a special bond. We do 5K walks annually in memory of our sons. On Mother’s Day, we took our families to Ojai together.

The Tragedy of Brandon

Leah said to our group back in 2012, “My son died of mental illness.” I didn’t say much, initially, but as the story unfolded and there was no history of psychosis in either family line, I thought marijuana had somehow played a role. I followed a hunch and began asking more questions. She looked at Brandon’s journals and saw his entries. “Am I having drug withdrawals?” he asked, trying to explain his racing thoughts. When he had to be hospitalized, he was convinced his lungs weren’t working.

Brandon died of suicide after being released from a three-day psych hold while experiencing psychotic symptoms tinged with mania (Guess what drug he had stopped using two weeks before entering the hospital…that’s right– cannabis). Despite telling numerous people in the hospital that he had just stopped marijuana use, none of the hospital staff raised a red flag that he was experiencing drug withdrawal symptoms. After Brandon left the hospital, he was convinced he needed a lung transplant despite doctors telling him there was nothing wrong with his lungs. He felt his breathing wasn’t right and was convinced he had caused it because he hadn’t stopped smoking cigarettes.

Brandon had become manic about four months earlier while smoking pot. When his mom expressed concern that he was becoming addicted, he just laughed because pot was a natural herb, not part of big drug companies making big $. Unfortunately Leah wasn’t aware that it’s best to come off pot gradually, under supervision. Unless psychiatrists are also certified for addiction treatment, they often don’t recognize marijuana withdrawal. Brandon had taken it upon himself to get a “medical marijuana” card, because he was having “anxiety.” Leah didn’t mind at the time, despite Brandon’s youth and undeveloped brain. As long as a doctor authorized it, she reasoned that it must be safe and legitimate. Before that time, he was using synthetic marijuana, which had alarmed her.

How Marijuana Becomes the Problem

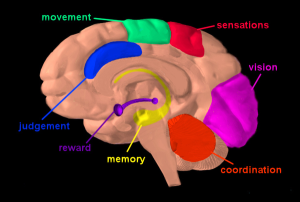

Sorry, but I want to share what I truly believe is happening in every town across America, not just to my son, to Lee/ Leah’s son. If Leah and I hadn’t met, she would have accepted “Brandon died of a mental illness.” Rather than telling our children they should avoid having children and blaming it all on faulty genes, as some medical practitioners would advise, consider the environmental effects like marijuana. I think you should advise any child, teen or young adult to practice optimal brain health and avoid all substances that strongly alter the brain. The medical evidence is the marijuana manipulates the brain more than any other drug.

Before my son had his first psychotic episode in 2009, he suffered a terrible knee injury in a boating accident that same year. It required knee surgery and 9 months of physical rehab. It’s likely that Ryan started using a lot more marijuana to treat “pain” just as the medical marijuana advocates suggest — without giving any regards to proper dosing, strength and time intervals that a pharmacy is required to give. He was living with his fiancée at the time, so we were not aware of this choice, or that he had already been using marijuana for about three years. The accident, surgery and pain were the perfect excuse for him to use a lot more marijuana–plus he wouldn’t take the pain meds because they gave him nausea. Pot was apparently the treatment he chose, but we didn’t know it.

So the pattern emerges–using marijuana for a few years, increase the usage for “medical” reasons (in this case an accident followed by surgery and pain), and, then at some point — psychosis.

Close to Home: Amanda Bynes

Another example of the marijuana – psychosis pattern is former child star Amanda Bynes. She went to the same high school as my son; they were born in the same year, but one year apart in school.

Last year she was in treatment at the same psychiatric hospital in Pasadena where Ryan had been at one time. I don’t know her or her parents, but I heard she had some excellent treatment there (wish my son had been treated as well). Afterwards, her parents had a one-year conservatorship for her. Her mother asserted that the effects of marijuana were her main psychiatric problem, not bipolar or schizophrenia, as had been a rumored.

Amanda Bynes did well and looked amazing during most of 2014, until her parents’ conservatorship ended. Then in late summer, when the hold had ended, Amanda had some episodes and accused her father of terrible things. How could that young woman, who had heard that THC alters brain chemistry while in rehabilitation, return to using pot again? The relapse speaks volumes as to how addictive marijuana really is, and how marijuana use alters brain chemistry.

Like Amanda Bynes, Ryan seemed completely healthy to us after his “first episode” of psychosis. Both Amanda Bynes and Ryan went back to the same drug that damaged their young minds. No one knows which brains will unravel with marijuana. Is the risk worth it for anyone? In this country, I’ve found a few psychiatrists, Dr. Stuart Gitlow of Rhode Island, Dr. Christian Thurstone in Denver, Dr. Thomas Carter in Seattle, and some psychologists, who understand the link between marijuana use and mental health problems. Mental health treatment and addiction treatment need to be aligned more closely. A Postscript describes when and how to stop these problems.